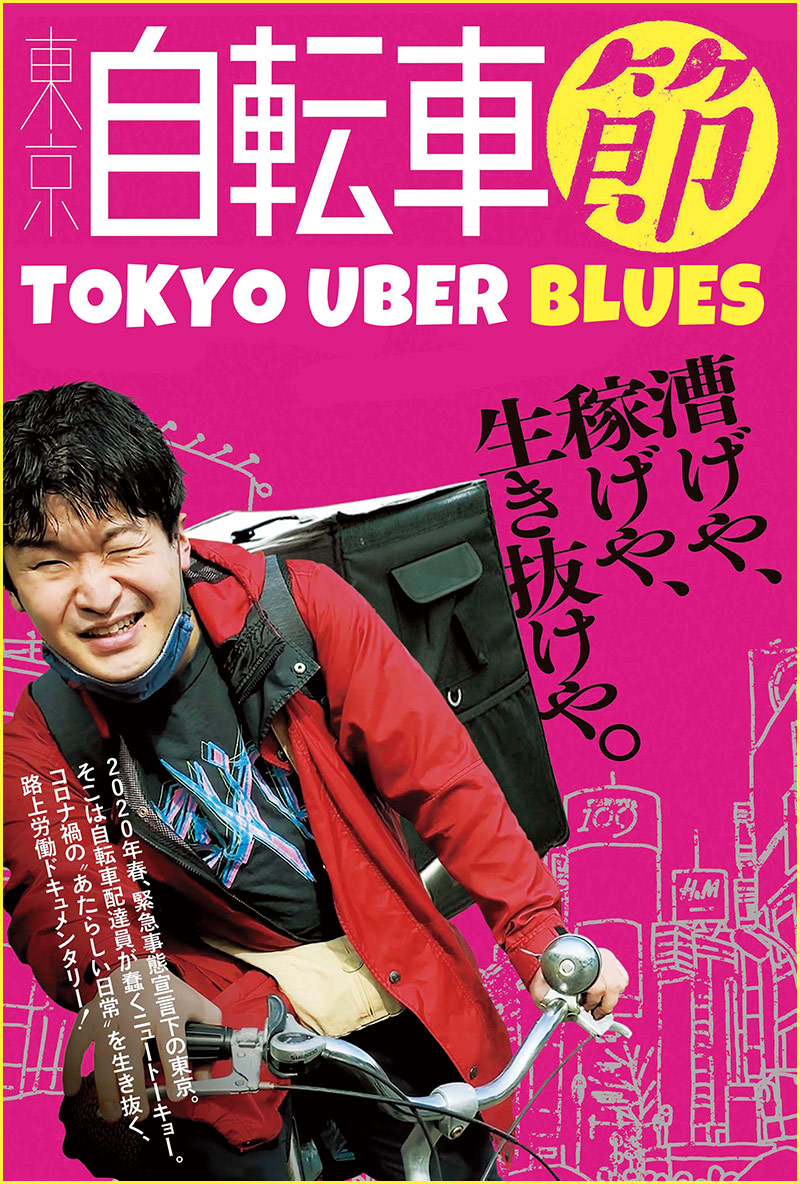

A view of Tokyo

from a speeding Uber Eats delivery bike:

about gig-economy labor,

the meaning of life,

and a burnt-out city

2022 | JAPAN | Documentary | DCP | in Japanese with English subtitles | 93 min

Director:Taku AOYAGI -- first feature

Producer:Kazuo OSAWA (nondelaico)

Cinematography:Taku AOYAGI, Kiyoshi TSUJII, Kazuo OSAWA

Editing:Kiyoshi TSUJII

Production Companies:Nondelaico, Mizuguchiya Film

International Liaison: IMPLEO Inc.

Director:Taku AOYAGI -- first feature

Producer:Kazuo OSAWA (nondelaico)

Cinematography:Taku AOYAGI, Kiyoshi TSUJII, Kazuo OSAWA

Editing:Kiyoshi TSUJII

Production Companies:Nondelaico, Mizuguchiya Film

International Liaison: IMPLEO Inc.

【SHORT SYNOPSIS】

The pandemic forces the filmmaker, a film-school graduate with a $40,000 student debt, out of a job. He decides to try his luck in Tokyo, joining the fleet of Uber Eats delivery bikers who cater to the big city in pseudo-lockdown. With just a bicycle and a smartphone, he is now able to earn whenever he likes. He’s helping people out, and it’s fun -- what a game! But when he realizes the system has the upper hand, he starts to think twice about the endless deliveries of tapioca milkshakes to closed doors in high-rise condos.

【LONGER SYNOPSIS】

When his job disappears due to the pandemic, 26-year old filmmaker Taku decides to try his luck in Tokyo, joining the fleet of Uber Eats food delivery bikers who cater to the big city in pseudo-lockdown. With just a bicycle and a smartphone, he is now able to earn-- he can decide his own work hours, he is free to choose or not choose to take orders. Taku is pleased that he can be of service to people in this time of anxiety. And it’s fun, like a game! But pedaling through deserted streets and delivering tapioca to closed doors in high-rise condos, he starts to wonder. What was it Ken Loach said about the Uberization of society? Why does he find himself sleeping on the streets with just coins in his pocket?Filming on smartphones and GoPros, Taku allows the audience to join his daily journey on wheels speeding through deserted Tokyo streets and to listen in as he talks to himself and with others of his generation. From the perspective of an unemployed young Japanese millennial who has a $40,000 student debt, does the Uber work model offer a future?

【DIRECTOR'S STATEMENT】

The allure of the Uber Eats game, the sensation of becoming a slave tothealgorithm,the pockets of oases in the Tokyo burnt-out desert! I was totally fascinated. But soon the joyful discovery of a new way of life was overtaken by uneasiness, asmyblackUber backpack (the “black box”) started weighing me down. I couldn’t helpseeingthedifference between the rosy picture upheld by corporations and the state, andthedesperation we on the street were living. My own behavior as a typical Japanesemillennialwas also on display, as I avoided raising issue and indulged in self-blaming andsolitarygrumbling.

I made this film so that you and I will not forget that our labor has value and that we are alive, even in this unforgiving world.

I made this film so that you and I will not forget that our labor has value and that we are alive, even in this unforgiving world.

【INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR Taku Aoyagi】

Q: Why did you start making this film?

In the beginning it was Kazuo Osawa, documentary producer and my senior from film school. He suggested I try filming while doing gig work and I immediately thought, "Yes, that’s it!” I hadanoutstanding5.5 million yen scholarship debt, had just lost my job driving drunk people home, and all filmmaking work had dried up with the pandemic. With no income, my first priority was to earn money. But I didn’t want to look for a regular job. I thought that Uber Eats could let me earn money quickly and work freely, and that would suit me fine.

Of course, as a documentary filmmaker, I was interested in filming Tokyo’s empty streets during the pandemic. From the perspective of a bicycle deliveryman, I might discover something. I had nothing to lose, with no name, no job, and no money.

Around March 2020, people in my hometown Yamanashi believed that anyone who went to Tokyo would contract the Corona virus, and I felt that fear. The authorities were requesting that people refrain from crossing prefecture lines. But my friends in Tokyo told me that people were commuting by train and going out shopping as usual, and that young people don’t get sick even when infected. I decided to make the trip from Yamanashi to Tokyo on a one-way ticket. I swore to myself that I would not return until the pandemic was over so as not to bring the virus back home.

Q: You filmed only with your smartphone and GoPros, why is that?

I'm basically on my own making deliveries, and I can’t really hold a camera while biking. Earning money was my priority, so the filming equipment had to be minimum. I used a smartphone small enough to fit in my pocket to quickly capture everyday moments, and GoPro action cameras to create a powerful sense of movement on the speeding bike. Selfie documentaries used to be filmed on small video cameras, but today the smartphone feels right. The project has this YouTuber feel, so I did some research on how bike delivery YouTubers shoot their videos.

Q: What was it actually like, delivering Uber Eats?

At first I thought I could earn more, but I worked all day and was not making much more than 50 bucks.

Then I learned some tricks. For example, it’s best to wait in front of McDonald’s; you should go off line and get back downtown after delivering to a residential area if you want to maximize profit; you should only work on rainy days or during lunch and dinner hours. You should learn the names of the condos so that you don’t lose time looking at the map. Thanks to the advice I got, I gradually started earning money.

Most of the customers requested doorstep drop-off, where I’d leave the delivery in front of their doors. I guess people use Uber Eats because they want to avoid contact with others, but I felt lonely that I couldn't meet the people I was delivering to. It felt like being a robot in the system. Although there was that sense of freedom and exhilaration of riding a bicycle through the city and seeing the most beautiful views from the upper floors of high rise condos.

When you get used to it and start earning, there’s this urge to challenge yourself with the game designed in the app. I became engrossed in completing The Quest, which provides rewards when you meet certain delivery goals. You hear about bad behavior by the bikers, but I think some of it is caused by the Uber Eats system which encourages cut-throat competition.

Q: It’s easy to join, but there are labor issues. As a worker, how did you feel about this?

There's no problem if it’s just a side job to earn extra money or to lose weight. But the pandemic seems to have expanded the number of people who are just desperate for a buck, in a very short-sighted way. Bicycles need maintenance, the Uber Eats bag costs about 5,000 yen, and there’s a lot of unexpected expenses in this job. Fortunately, I haven't been injured so far, but I’ve had to pay for damage to my phone, break age due to rain, theft of the phone holder on my bike, flat tires, worn out brakes, and so on. The costs were a big blow.

Uber Eats delivery staff are considered independent contractors and are not covered by the workers insurance stipulated by labor laws which say, “if a company makes a profit from the work of its workers, it should also bear the risks they incur.” In France and the UK, gig workers are recognized as employees and there are laws that rightfully address these issues, but Japan has yet to develop it sown legislation. Uber can also slash delivery commission at will. We are living out film director Ken Loach's warning that we are, after all, being pushed around as disposable labor.

Q: In the film, we see you encounter different people.

Making a film during this “stay-home” pandemic meant that engagement with people would be crucial. I first thought I would meet people at pickup points, interact with other delivery people, and meet people who ordered the food. But surprisingly these encounters were few and far between. The people I actually met were those who approached me out of concern or people I met by chance during my breaks. This left a strong impression on me.

My old friends immediately understood why I had a camera, so they opened up to me. The aspiring film director Takano had been doing the Uber gig for quite some time, so he was the one who gave me advice. Tsuchi was the typical Covid paranoid who discovered all the ways to enjoy his “stay-home” confinement. My senior Sachiho-san gave me and herself words of support and encouragement. Former high school classmates Iimuro and Tasuku shared their current state of life with me.

We were born around 1993 -- the generation educated under the new school curriculum that emphasized less cramming and more creative thinking. We were taught that each of us was special (the “only one”) and there was no need to aim for the “number one.” We were allowed to grow up in an environment that respects individuality and independence. I honestly think that is a good thing, but the foundations of Japanese society were already laid by the older generation that demands that you hustle for number one. There are lots of us who are struggling with this contradiction -- we were taught to value individuality in a competitive society that doesn’t care for difference. It seems like the pandemic just made this obvious.

It was by chance that I met the actor Mr Kato and the elderly lady in the park, both of whom approached me when I was sitting all alone on a public bench. Mr Kato told me he’s an actor for many years and his dream was to become a star. Maybe the young Mr Kato is me today. It made me think how tough it is to commit yourself to the lifestyle you love. As for the granny, she told me stories about the war at length even before I started filming. At first I considered her stories nothing to do with this film, but simply as valuable testimony that should be recorded. It was only later that I made the connection between her story and the state of Japan today.

Q: It’s striking how you caricatured yourself in the film. What was your aim?

Really? To be honest, it was never intentional. But maybe it feels like a farce because I had a singular focus: earning money. The pandemic regulations demanded that people don’t go out of their homes without a good reason, so the idea of frivolously filming was not on my mind. But I definitely needed to earn money immediately. It was not easy and rather scary to go out to work in this situation, but the reality of not doing so was equally drab. In this Catch-22 situation, turning the camera on myself and my problems could perhaps let the viewer laugh anxiety away. With this hope in mind, I decided to film every question and discovery that I encountered.

Personality-wise, I’m not the type to point out problems or angrily denounce them. I tend to laugh and accept things as they come, even if unreasonable. But as I pressured myself to toil for income, my subconscious spilled out. There was truth in what came out of my mouth during the scene where I exhaust my strength to the limit to complete the Quest. In fact I hardly remember how I filmed that. The last part has an atmosphere akin to The Dark Knight or Joker -- I think I definitely had an accumulated sense of discomfort and resentment to wards society at that moment. I have to say, I hadn't seen myself smile that beautifully in a long time. I never thought there would be laughter at the end of madness, and I think it was a horrible situation, just like Joker. I'm glad I made it into a film. What would have happened if I hadn't been film making...? I prefer not to think about that.

Q: In the second half, you shift from your personal life to the social backdrop of the pandemic. Words like “the system”, “bombed to the ground” and “loneliness” strike a chord.

I was never a good student, so I always found it hard to discuss social issues or politics. Before this, I would never have thought of using terms like "bombed to the ground" or to talk about “everyone lonely”. But in the act of capturing my surroundings carefully with the camera, and riding the emotional roller coaster, I got a sense of what kind of system I was operating in, and how it was controlling me. I also realized that this was a system with out a pulsing heart, and moreover that the world was full of such systems that just pursue profit. That's when it all became clear to me. For some time now, I’ve been feeling a lot of disconnect in my life. When I returned to my home town in Yamanashi, none of my friends were around. I never saw them even at the local festivals. The only way I could check in on them was through social media, and I found I almost forgot about friends who were not using social media. When we were kids, we used to go to each others’ front doors and just yell when we wanted to play together, but now a days you would never go without an appointment. It’s as if social networks and other “systems”(created by people we don't know) made everyone lonely. When the old lady told me how Tokyo was totally flattened during the war, it suddenly occurred to me that our inner world today was similarly being “firebombed” even if the buildings were still standing. I wanted to make that clear to myself by daring to state it in the film. At the very least, things could get better if we are conscious of the fact.

I believe labor in principle should be organic -- something with blood flowing through it. In the film, I tried to show how even the AI-controlled system can be a place where real people with human warmth work. Trying to treat customers personally and with care may seem absurd in a service where faces are masked and people ask for doorstep drop-off. But in defiance of the system that is designed to modify our behavior for maximized efficiency and profit, that turns us unwittingly into robots, making our selves a ware of our isolation from each other could maybe kindle the desire for encounters and connection. The Japanese title of Tokyo Uber Blues is “Tokyo Bicycle Tune”. “Tune (bushi)” came from the term used often for traditional folk and labor songs. Like the songs of sweating miners that empowered those who sang them, I wanted to make bike delivery work into something more human, with a beating heart. Thus the title.

In the beginning it was Kazuo Osawa, documentary producer and my senior from film school. He suggested I try filming while doing gig work and I immediately thought, "Yes, that’s it!” I hadanoutstanding5.5 million yen scholarship debt, had just lost my job driving drunk people home, and all filmmaking work had dried up with the pandemic. With no income, my first priority was to earn money. But I didn’t want to look for a regular job. I thought that Uber Eats could let me earn money quickly and work freely, and that would suit me fine.

Of course, as a documentary filmmaker, I was interested in filming Tokyo’s empty streets during the pandemic. From the perspective of a bicycle deliveryman, I might discover something. I had nothing to lose, with no name, no job, and no money.

Around March 2020, people in my hometown Yamanashi believed that anyone who went to Tokyo would contract the Corona virus, and I felt that fear. The authorities were requesting that people refrain from crossing prefecture lines. But my friends in Tokyo told me that people were commuting by train and going out shopping as usual, and that young people don’t get sick even when infected. I decided to make the trip from Yamanashi to Tokyo on a one-way ticket. I swore to myself that I would not return until the pandemic was over so as not to bring the virus back home.

Q: You filmed only with your smartphone and GoPros, why is that?

I'm basically on my own making deliveries, and I can’t really hold a camera while biking. Earning money was my priority, so the filming equipment had to be minimum. I used a smartphone small enough to fit in my pocket to quickly capture everyday moments, and GoPro action cameras to create a powerful sense of movement on the speeding bike. Selfie documentaries used to be filmed on small video cameras, but today the smartphone feels right. The project has this YouTuber feel, so I did some research on how bike delivery YouTubers shoot their videos.

Q: What was it actually like, delivering Uber Eats?

At first I thought I could earn more, but I worked all day and was not making much more than 50 bucks.

Then I learned some tricks. For example, it’s best to wait in front of McDonald’s; you should go off line and get back downtown after delivering to a residential area if you want to maximize profit; you should only work on rainy days or during lunch and dinner hours. You should learn the names of the condos so that you don’t lose time looking at the map. Thanks to the advice I got, I gradually started earning money.

Most of the customers requested doorstep drop-off, where I’d leave the delivery in front of their doors. I guess people use Uber Eats because they want to avoid contact with others, but I felt lonely that I couldn't meet the people I was delivering to. It felt like being a robot in the system. Although there was that sense of freedom and exhilaration of riding a bicycle through the city and seeing the most beautiful views from the upper floors of high rise condos.

When you get used to it and start earning, there’s this urge to challenge yourself with the game designed in the app. I became engrossed in completing The Quest, which provides rewards when you meet certain delivery goals. You hear about bad behavior by the bikers, but I think some of it is caused by the Uber Eats system which encourages cut-throat competition.

Q: It’s easy to join, but there are labor issues. As a worker, how did you feel about this?

There's no problem if it’s just a side job to earn extra money or to lose weight. But the pandemic seems to have expanded the number of people who are just desperate for a buck, in a very short-sighted way. Bicycles need maintenance, the Uber Eats bag costs about 5,000 yen, and there’s a lot of unexpected expenses in this job. Fortunately, I haven't been injured so far, but I’ve had to pay for damage to my phone, break age due to rain, theft of the phone holder on my bike, flat tires, worn out brakes, and so on. The costs were a big blow.

Uber Eats delivery staff are considered independent contractors and are not covered by the workers insurance stipulated by labor laws which say, “if a company makes a profit from the work of its workers, it should also bear the risks they incur.” In France and the UK, gig workers are recognized as employees and there are laws that rightfully address these issues, but Japan has yet to develop it sown legislation. Uber can also slash delivery commission at will. We are living out film director Ken Loach's warning that we are, after all, being pushed around as disposable labor.

Q: In the film, we see you encounter different people.

Making a film during this “stay-home” pandemic meant that engagement with people would be crucial. I first thought I would meet people at pickup points, interact with other delivery people, and meet people who ordered the food. But surprisingly these encounters were few and far between. The people I actually met were those who approached me out of concern or people I met by chance during my breaks. This left a strong impression on me.

My old friends immediately understood why I had a camera, so they opened up to me. The aspiring film director Takano had been doing the Uber gig for quite some time, so he was the one who gave me advice. Tsuchi was the typical Covid paranoid who discovered all the ways to enjoy his “stay-home” confinement. My senior Sachiho-san gave me and herself words of support and encouragement. Former high school classmates Iimuro and Tasuku shared their current state of life with me.

We were born around 1993 -- the generation educated under the new school curriculum that emphasized less cramming and more creative thinking. We were taught that each of us was special (the “only one”) and there was no need to aim for the “number one.” We were allowed to grow up in an environment that respects individuality and independence. I honestly think that is a good thing, but the foundations of Japanese society were already laid by the older generation that demands that you hustle for number one. There are lots of us who are struggling with this contradiction -- we were taught to value individuality in a competitive society that doesn’t care for difference. It seems like the pandemic just made this obvious.

It was by chance that I met the actor Mr Kato and the elderly lady in the park, both of whom approached me when I was sitting all alone on a public bench. Mr Kato told me he’s an actor for many years and his dream was to become a star. Maybe the young Mr Kato is me today. It made me think how tough it is to commit yourself to the lifestyle you love. As for the granny, she told me stories about the war at length even before I started filming. At first I considered her stories nothing to do with this film, but simply as valuable testimony that should be recorded. It was only later that I made the connection between her story and the state of Japan today.

Q: It’s striking how you caricatured yourself in the film. What was your aim?

Really? To be honest, it was never intentional. But maybe it feels like a farce because I had a singular focus: earning money. The pandemic regulations demanded that people don’t go out of their homes without a good reason, so the idea of frivolously filming was not on my mind. But I definitely needed to earn money immediately. It was not easy and rather scary to go out to work in this situation, but the reality of not doing so was equally drab. In this Catch-22 situation, turning the camera on myself and my problems could perhaps let the viewer laugh anxiety away. With this hope in mind, I decided to film every question and discovery that I encountered.

Personality-wise, I’m not the type to point out problems or angrily denounce them. I tend to laugh and accept things as they come, even if unreasonable. But as I pressured myself to toil for income, my subconscious spilled out. There was truth in what came out of my mouth during the scene where I exhaust my strength to the limit to complete the Quest. In fact I hardly remember how I filmed that. The last part has an atmosphere akin to The Dark Knight or Joker -- I think I definitely had an accumulated sense of discomfort and resentment to wards society at that moment. I have to say, I hadn't seen myself smile that beautifully in a long time. I never thought there would be laughter at the end of madness, and I think it was a horrible situation, just like Joker. I'm glad I made it into a film. What would have happened if I hadn't been film making...? I prefer not to think about that.

Q: In the second half, you shift from your personal life to the social backdrop of the pandemic. Words like “the system”, “bombed to the ground” and “loneliness” strike a chord.

I was never a good student, so I always found it hard to discuss social issues or politics. Before this, I would never have thought of using terms like "bombed to the ground" or to talk about “everyone lonely”. But in the act of capturing my surroundings carefully with the camera, and riding the emotional roller coaster, I got a sense of what kind of system I was operating in, and how it was controlling me. I also realized that this was a system with out a pulsing heart, and moreover that the world was full of such systems that just pursue profit. That's when it all became clear to me. For some time now, I’ve been feeling a lot of disconnect in my life. When I returned to my home town in Yamanashi, none of my friends were around. I never saw them even at the local festivals. The only way I could check in on them was through social media, and I found I almost forgot about friends who were not using social media. When we were kids, we used to go to each others’ front doors and just yell when we wanted to play together, but now a days you would never go without an appointment. It’s as if social networks and other “systems”(created by people we don't know) made everyone lonely. When the old lady told me how Tokyo was totally flattened during the war, it suddenly occurred to me that our inner world today was similarly being “firebombed” even if the buildings were still standing. I wanted to make that clear to myself by daring to state it in the film. At the very least, things could get better if we are conscious of the fact.

I believe labor in principle should be organic -- something with blood flowing through it. In the film, I tried to show how even the AI-controlled system can be a place where real people with human warmth work. Trying to treat customers personally and with care may seem absurd in a service where faces are masked and people ask for doorstep drop-off. But in defiance of the system that is designed to modify our behavior for maximized efficiency and profit, that turns us unwittingly into robots, making our selves a ware of our isolation from each other could maybe kindle the desire for encounters and connection. The Japanese title of Tokyo Uber Blues is “Tokyo Bicycle Tune”. “Tune (bushi)” came from the term used often for traditional folk and labor songs. Like the songs of sweating miners that empowered those who sang them, I wanted to make bike delivery work into something more human, with a beating heart. Thus the title.

【CONTACT】

Asako FUJIOKA (Documentary Dream Center/IMPLEO Inc.)

IMPLEO Inc.11-6 Maruyama-cho, Shibuya-ku 150-0044 Japan

Email:info@ddcenter.org